I finally succumbed recently to buying and using a wearable; one of those watches that works in concert with your mobile phone to track various measures for health and fitness (such as heart rate and step count). I must also admit to getting rather fanatical since the purchase on attaining my 10,000 steps per day target.

The number of steps to be taken each day had previously held little significance for me as they seldom featured in any key guidelines from major fitness bodies (for instance, ACSM). I latched onto this 10,000 steps per day target as it had been cited by so many people for so long, and made the assumption (somewhat erroneously as it turned out) that there was an underpinning evidence-base to justify this number.

In light of this new obsession, imagine my surprise when I looked at the cover of a recent issue of the New Scientist (15 June 2019) and saw the headline “How much exercise do we really need? … Spoiler alert: it’s not 10,000 steps)”. I naturally had to read this excellent article by the anthropologist Herman Pontzer, who adopted a refreshing perspective when describing the quantity and quality of physical activity/exercise we actually need.

Whilst the vast majority of its content was congruent with my existing knowledge-base, there was one piece of information that immediately stood out; namely, that the 10,000 steps per day target was originally a marketing ploy from a Japanese manufacturer of early pedometers around the time of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. A little further research revealed it was called Manpo-Kei (which literally translates as 10,000 steps meter) and was developed by Dr Yoshiro Hatano with the aim of increasing step count to 10,000 from the average of 2,500 to 5000 at that time, which he believed would result in additional calorie expenditure and lower risk of heart disease. By all accounts, this was an arbitrary number that didn’t really have any evidence to justify it, but despite this, it has become part of popular culture and the World Health Organisation and various countries have adopted it as part of their national guidelines anyway.

Another consequence of reading this article was that I kicked myself for blindly accepting this number despite possessing the knowledge that would suggest otherwise. The universally accepted 150+ minutes a week of moderate or 75+ minutes a week of vigorous intensity physical activity, in bouts of 10 minutes or more, give us our clue here. Pontzer (2019) states that many of our steps just don’t count as moderate or vigorous intensity, and therefore do not contribute substantially to our health and fitness; he states that 3000 moderate or vigorous intensity steps would be equivalent to 10,000 steps on a fitness tracker.

By way of illustration, I clocked up over 3000 steps teaching one day last week – I was presenting from the front of the class and didn’t really do anything physical other than walking a few paces here and there on occasion. At no point was my heart pounding, breathing difficult, or sweat produced. As Pontzer (2019) states, low intensity steps still get you moving and it’s far better than the sedentary alternative, but pottering round the house, for example, gaining a few steps here and a few steps there is unlikely to yield the same benefits as, say, a brisk 30-minute walk.

Sustained walking at the appropriate intensity would therefore seem to be more important. An excellent article published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine (https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/bjsports/52/12/776.full.pdf) by Tudor-Locke and colleagues investigated how fast we should actually be walking to maximise health benefits. They concluded we should adopt a cadence (the rate at which you walk) of 100 or more steps per minute to maximise health benefits for adults.

Is 10,000 steps a day wrong then? What should it be?

There doesn’t seem to be a straightforward or clear answer published anywhere. For some people, 10,000 steps a day can seem quite daunting or unattainable. For example, on days when I am stuck behind the computer, completing 10,000 steps can prove extremely challenging. For older or deconditioned individuals and for those with chronic conditions it may be a step too far (initially at least).

Pontzer (2019) in his New Scientist article states the optimum amount of exercise we need each day is equivalent to about 15,000 steps at a brisk walking pace or faster – about 2 hours worth! He adds that that lower intensity steps will count for less. This would seem even more intimidating and unfeasible.

The UK’s National Obesity Forum (http://www.nationalobesityforum.org.uk/index.php/healthcare-professionals/treatment-mainmenu-169/192-useful-tools-and-agencies.html) suggest that 3,000-6,000 steps per day indicates you are sedentary, 7,000-10,000 steps per day suggests you are moderately active, and 11,000 or more steps per day implies you are very active. It doesn’t, however, state where it got these figures from, or the evidence-base.

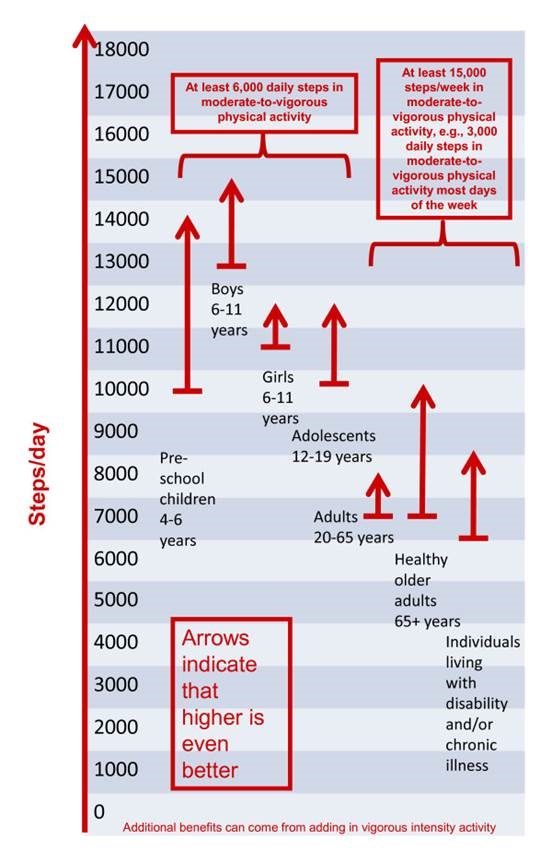

The International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3197470/) published an article asking how many steps a day are enough. The diagram below shows their recommendations:

I’ll give the final word to ACSM. In 2019, they published their take on the daily step count (https://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/fulltext/2019/06000/Daily_Step_Counts_for_Measuring_Physical_Activity.15.aspx#pdf-link) and (https://www.acsm.org/blog-detail/acsm-certified-blog/2019/06/14/walking-10000-steps-a-day-physical-activity-guidelines). They state that counts ranging from 7000 to 9000 steps a day are equivalent to the 150 to 300 minutes a week of moderate-vigorous activity and may accrue the same health benefits. They also state more research is needed before any specific public health guidelines can be formulated, but, in general, accumulating more steps every day is better. They conclude that national guidelines suggest we should all move more and sit less, and as walking is easy and free, the more walking we do the better.